In 1900, a photograph was taken at Yasnaya Polyana depicting Russian writers Leo Tolstoy and Maxim Gorky. Yasnaya Polyana was Tolstoy's estate near Tula, Russia, where he lived and worked on his literary masterpieces. The photograph captured a moment of literary significance, showcasing two of Russia's most influential writers of the time. Leo Tolstoy, renowned for his epic novels such as "War and Peace" and "Anna Karenina," was a prominent figure in Russian literature and philosophy. Maxim Gorky, a celebrated playwright and author known for works like "The Lower Depths," was a leading voice of social realism in Russian literature.

The meeting of Tolstoy and Gorky at Yasnaya Polyana in 1900 likely involved discussions on literature, philosophy, and social issues, reflecting their shared

commitment to literature's transformative power and social justice. The photograph by S. A. Tolstaya not only captured a personal moment between these literary giants but also marked a significant intersection of their ideas and influences during a pivotal period in Russian cultural history.

#usa #explore #history #usahistoy

2023年,繼白鯨記討論,有拿破崙電影,跟曹老師說想好好重讀它。送我一套二本。沒好好讀。

2016年4月9日 星期六

Leo Tolstoy 托爾斯泰:War and Peace ;《藝術論》"What Is Art?" ;The Cossacks. Tolstoy and His Problems

"This black-eyed, wide-mouthed girl, not pretty but full of life . . . ran to hide her flushed face in the lace of her mother’s mantilla—not paying the least attention to her severe remark—and began to laugh. She laughed, and in fragmentary sentences tried to explain about a doll which she produced from the folds of her frock."

--from WAR AND PEACE

\https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=bbc+war+and+peace

Leo Tolstoy's 186th birthday: Here's War and Peace in 186 words

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"What Is Art?" (Russian: Что такое искусство? [Chto takoye iskusstvo?]; 1897) is an essay by Leo Tolstoy in which he argues against numerous aesthetic theories which define art in terms of the good, truth, and especially beauty. In Tolstoy's opinion, art at the time was corrupt and decadent, and artists had been misled.

"Art is a human activity having for its purpose the transmission to others of the highest and best feelings to which men have risen."

--from "What is Art?" (1896) by Leo Tolstoy

During the decades of his world fame as sage & preacher as well as author of War & Peace & Anna Karenin, Tolstoy wrote prolifically in a series of essays & polemics on issues of morality, social justice & religion. These culminated in What is Art?, published in 1898. Altho Tolstoy perceived the question of art to be a religious one, he considered & rejected the idea that art reveals & reinvents thru beauty. The works of Dante, Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Beethoven, Baudelaire & even his own novels are condemned in the course of Tolstoy's impassioned & iconoclastic redefinition of art as a force for good, for the improvement of humankind.

托爾斯泰《藝術論》耿濟之譯,台北:晨鐘,1972/82,

此譯本可能有不少小錯譬如說 p.28/95 Schiller 雪萊/席勒

上周末,台北懷恩堂有一場關於此論文的解說會. 我缺席.本書以"基督教藝術的任務就是實現人類友愛的連合."為結語.

第十卷

本卷包括根據英國倍因(Robert Nisbet Bain,通譯貝恩)的英譯本Russian Fairy Tales(一八九二年)選譯的《俄羅斯民間故事》,根據培因(即倍因)的英譯本Cossack Fairy Tales and Folk-Tales(一八九四年)選譯的《烏克蘭民間故事》,根據英國韋格耳(Arthur Edward Pearse Brome Weigall,通譯韋戈爾)所著傳記Sappho of Lesbos: Her Life and Times (一九三二年)編譯的《希臘女詩人薩波》,英國勞斯(William Henry Denham Rouse)著神話故事《希臘的神與英雄》(Gods, Heroes and Men of Ancient Greece,一九三四年),以及“其他英文和世界語譯作”。

《俄羅斯民間故事》譯於一九五二年五月,一九五二年十一月由香港大公書局出版,署“知堂譯”。一九五七年八月天津人民出版社重印此書,署“周啟明譯”。

"I asked myself: 'Is it possible to love a woman who will never understand the profoundest interests of my life? Is it possible to love a woman simply for her beauty, to love the statue of a woman?' But I was already in love with her, though I did not yet trust to my feeling."

--from "The Cossacks" by Leo Tolstoy

A brilliant short novel inspired by Leo Tolstoy’s experience as a soldier in the Caucasus, The Cossacks has all the energy and poetry of youth while also foreshadowing the great themes of Tolstoy’s later years. His naïve hero, Olenin, is a young nobleman who is disenchanted with his privileged and superficial existence in Moscow and hopes to find a simpler life in a Cossack village. As Olenin foolishly involves himself in their violent clashes with neighboring Chechen tribesmen and falls in love with a local girl, Tolstoy gives us a wider view than Olenin himself ever possesses of the brutal realities of the Cossack way of life and the wild, untamed beauty of the rugged landscape. This novel of love, adventure, and male rivalry on the Russian frontier—completed in 1862, when the author was in his early thirties—has always surprised readers who know Tolstoy best through the vast, panoramic fictions of his middle years. Unlike those works, The Cossacks is lean and supple, economical in design and execution. But Tolstoy could never touch a subject without imbuing it with his magnificent many-sidedness, and so this book bears witness to his brilliant historical imagination, his passionately alive spiritual awareness, and his instinctive feeling for every level of human and natural life. READ an excerpt here:http://knopfdoubleday.com/book/179295/the-cossacks/

東方白的文學回憶錄【真與美】末卷,有專文介紹他與夫人訪此莊園的感動........

War and peaceful gardens: in the land of Tolstoy

A visit to Tolstoy’s country estate gives writer and gardener Charlotte Mendelson an insight into the relationship between nature and creativity

Country life … Tolstoy in the grounds of his estate, Yasnaya Polyana. Photograph: George Rinhart/Corbis/Getty

Country life … Tolstoy in the grounds of his estate, Yasnaya Polyana. Photograph: George Rinhart/Corbis/Getty

Charlotte Mendelson

Saturday 15 October 2016 11.00 BST

Springtime can kill you, but autumn is worse. If one’s soul responds to nature – and, as Louis Armstrong said of jazz, if you have to ask what that means, you’ll never know – then its beauty is painful. Whatever TS Eliot thought (the poor man was wrong about so much), autumn is the most painful time of all. Walking in the grounds of Tolstoy’s country estate at Yasnaya Polyana, yellow birch leaves turning gently as they fall, is almost too much, particularly for an oversensitive novelist. Five of us are here, imported by the British Council to broaden Russian conceptions of British literature. We have worked – by God we have worked – but, this morning, among the wooded paths and ripe, rich leaf mould, nothing else seems to matter, not even fiction.

For cramped city-dwellers, the incomprehensible excess of space is dazzling: the “cascade of three ponds”, each more invitingly cool and swimmable than the last; the fir woods thick with fungal life; the juicy grass. Even the ponies have had a surfeit. There is so much silken birch bark, pinkly tender beneath its epidermis; so many fallen, unregarded apples and ancient, lichen-spattered branches: mustard, pigeon, rose. One wants to sniff and wallow; at least, I do. Surely this is normal? A reasonable response to being knee-deep in the dew and bracken: surrendering to the space, the wildness?

Of course not. My fellow writers return home with translators’ business cards and ecclesiastical souvenirs. My case is full of Japanese quinces, oak leaves, almond shells, calendula seeds and, most worrying of all, a knobbly fir branch, as long as my arm, stolen from the forest floor and slipped past the cold-eyed, epauletted customs boys at Domodedovo airport. Did the other novelists find themselves embarrassingly weeping at the perfect transparency of a plantation of firs, bare-trunked and widely spaced to allow, as Sofia and Leo Tolstoy had intended, the pale September sunlight to pour in? They did not.

***

Like his grandfather, Prince Volkonsky, who first developed the estate in Tula region, 120 miles south of Moscow, Leo Tolstoy was an enthusiast. His wife, Sofia, may also have been, in her spare moments between bearing his 13 children, copying and editing War and Peace seven times and documenting every minute of their lives in diaries and photographs. Sofia’s husband had no time for such fripperies. He was busy, trying to create a new breed of horse by crossing English thoroughbred stallions with their Kirgizian cousins; following developments in fruit-tree breeding; buying Japanese pigs (“I feel I cannot be happy in life until I get some of my own”); downing healthy bowlfuls of fermented mare’s milk; maddening Sofia with his “purely verbal” renunciation of worldly goods; spending too many roubles on attempting to grow watermelons, coffee and pineapples in his hothouse. Anything, one suspects, could have captured his attention: dog-racing, topiary, needlepoint.

Tolstoy derided his early works as an awkward mixture of fact and fiction, yet they offer an insight into what made him

"He stepped down, trying not to look long at her, as if she were the sun, yet he saw her, like the sun, even without looking."

--from "Anna Karenina" By Leo Tolstoy

A famous legend surrounding the creation of Anna Karenina tells us that Tolstoy began writing a cautionary tale about adultery and ended up falling in love with his magnificent heroine. It is rare to find a reader of the book who doesn’t experience the same kind of emotional upheaval. Anna Karenina is filled with major and minor characters who exist in their own right and fully embody their mid-nineteenth-century Russian milieu, but it still belongs entirely to the woman whose name it bears, whose portrait is one of the truest ever made by a writer. Translated by Louise and Aylmer Maude.

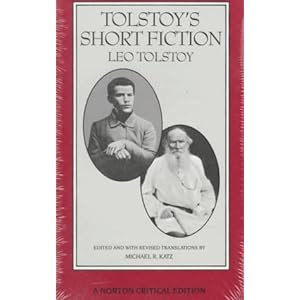

Leo Tolstoy’s short works, like his novels, show readers his narrative genius, keen observation, and historical acumen—albeit on a smaller scale. This Norton Critical Edition presents twelve of Tolstoy’s best-known stories, based on the Louise and Aylmer Maude translations (except “Alyosha Gorshok”), which have been revised by the editor for enhanced comprehension and annotated for student readers. The Second Edition newly includes “A Prisoner in the Caucasus,” “Father Sergius,” and “After the Ball,” in addition to Michael Katz’s new translation of “Alyosha Gorshok.” Together these stories represent the best of the author’s short fiction before War and Peace and after Anna Karenina.

“Backgrounds and Sources” includes two Tolstoy memoirs, A History of Yesterday (1851) and The Memoirs of a Madman (1884), as well as entries—expanded in the Second Edition—from Tolstoy’s “Diary for 1855” and selected letters (1858–95) that shed light on the author’s creative process.

“Criticism” collects twenty-three essays by Russian and western scholars, six of which are new to this Second Edition. Interpretations focus both on Tolstoy’s language and art and on specific themes and motifs in individual stories. Contributors include John M. Kopper, Gary Saul Morson, N. G. Chernyshevsky, Mikhail Bakhtin, Harsha Ram, John Bayley, Vladimir Nabokov, Ruth Rischin, Margaret Ziolkowski, and Donald Barthelme.

A Chronology of Tolstoy’s life and work and an updated Selected Bibliography are also included.

. --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Leo Tolstoy 托爾斯泰:War and Peace ;《藝術論》"What Is Art?" ;The Cossacks. Tolstoy and His Problems

"This black-eyed, wide-mouthed girl, not pretty but full of life . . . ran to hide her flushed face in the lace of her mother’s mantilla—not paying the least attention to her severe remark—and began to laugh. She laughed, and in fragmentary sentences tried to explain about a doll which she produced from the folds of her frock."

--from WAR AND PEACE

\https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=bbc+war+and+peace

Napoleon's determined bid to conquer Russia forms the background to War and Peace. The ensuing turmoil drives conflict and uncertainty for the books's core families. Paterson Joseph & John Hurt lead a stunning cast and Tolstoy provides the action in one of the world's greatest novels.

Download all ten episodes now > http://bbc.in/1IvVTz5

War and Peace is 150 this year. Sadie Stein on the history of its publication: http://bit.ly/1DCmtFS

2015 marks the sesquicentennial for Tolstoy’s classic—depending on how you count.

THEPARISREVIEW.ORG|由 TIERRA INNOVATION 上傳

BBC Radio 4

We can learn a lot about the art of living from Tolstoy's War and Peace but we can also learn from the life of the master novelist himself. Tolstoy was a member of the Russian nobility, and his early life of the young count was raucous, debauched and violent.

But he gradually weaned himself off his decadent, racy lifestyle and rejected the received beliefs of his aristocratic background, adopting a radical, unconventional worldview that shocked his peers. So how exactly might his personal journey help us rethink our own philosophies of life?

Tolstoy's Secret's For a Better Life http://bbc.in/1xzNta2

Catch up & download War and Peace http://bbc.in/1BniJGY

We can learn a lot about the art of living from Tolstoy's War and Peace but we can also learn from the life of the master novelist himself. Tolstoy was a member of the Russian nobility, and his early life of the young count was raucous, debauched and violent.

But he gradually weaned himself off his decadent, racy lifestyle and rejected the received beliefs of his aristocratic background, adopting a radical, unconventional worldview that shocked his peers. So how exactly might his personal journey help us rethink our own philosophies of life?

Tolstoy's Secret's For a Better Life http://bbc.in/1xzNta2

Catch up & download War and Peace http://bbc.in/1BniJGY

Catch up & download War and Peace http://bbc.in/1BniJGY

War and Peace, Tolstoy's epic drama set against Napoleon's invasion of Russia, took over the airwaves yesterday. It's an epic tale of love, loss, vanity, death, destruction and redemption. If you've always promised you'll read it but never quite got there - hear this.

Leo Tolstoy's 186th birthday: Here's War and Peace in 186 words

Because although we should read it from cover to cover, realistically…

What better way to celebrate the birthday of Leo Tolstoy than to read his monumentally weighty tome War and Peace…?

Well, for those who don't quite have time to get through all 561,093 words (Oxford World's Classics edition) of it,The Independent has produced its own marvellously abridged version.

So, on the 186th anniversary of Tolstoy's birth, here it is; in 186 words.

Petersburg, 1805: glitzy party at Anna Scherer’s. Napoleon is on the march. Kuragins? Flashy, dodgy crowd, especially minx Helene. Rostovs? Nice, penniless Moscow clan, with headstrong son, Nikolai.

Gauche, thoughtful Pierre Bezukhov: a count’s bastard, super-rich (when dad dies) but adrift. Unhappily wed Andrey Bolkonsky’s the real warrior toff, but those dark nights of the soul! Pierre marries flighty Helene.

Catastrophe! Rows, affair, duel, break-up (and Helene’s bad end) guaranteed. Andrey, Nikolai confront Napoleon at Austerlitz: Russian debacle. Widowed, Andrey falls for blooming Natasha, who’s ensnared by married cad Anatol Kuragin.

Do-gooding Pierre tries to save the world: fails.

1812: here’s fateful Napoleon again, making history (but what is history?), invading Russia. Bloody slaughter at Borodino; Russia resists. Andrey’s injured, Pierre a fugitive, then PoW. Rostovs flee as Moscow fall.

Amid the misery, Natasha grows up fast; Pierre too, helped by saintly peasant. Nikolai rescues Maria, the dying Andrey’s sister. Napoleon retreats. Hurrah!

Liberated, Pierre bonds with Natasha; Nikolai and Maria spliced. Poor cousin Sonya, Nikolai’s long-suffering intended! Two new families: happily ever after?

Almost but what does it all (time, history, freedom, destiny) really mean?

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Art is a human activity having for its purpose the transmission to others of the highest and best feelings to which men have risen."

--from "What is Art?" (1896) by Leo Tolstoy

During the decades of his world fame as sage & preacher as well as author of War & Peace & Anna Karenin, Tolstoy wrote prolifically in a series of essays & polemics on issues of morality, social justice & religion. These culminated in What is Art?, published in 1898. Altho Tolstoy perceived the question of art to be a religious one, he considered & rejected the idea that art reveals & reinvents thru beauty. The works of Dante, Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Beethoven, Baudelaire & even his own novels are condemned in the course of Tolstoy's impassioned & iconoclastic redefinition of art as a force for good, for the improvement of humankind.

托爾斯泰《藝術論》耿濟之譯,台北:晨鐘,1972/82,

此譯本可能有不少小錯譬如說 p.28/95 Schiller 雪萊/席勒

上周末,台北懷恩堂有一場關於此論文的解說會. 我缺席.本書以"基督教藝術的任務就是實現人類友愛的連合."為結語.

The task for Christian art is to establish brotherly union among men.

What Is Art

TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINAL MS., WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY AYLMER MAUDE

http://archive.org/stream/whatisart00tolsuoft/whatisart00tolsuoft_djvu.txt

英文本有附錄譯文為此本漢譯所略去

Tolstoy and His Problems - Page 38 - Google Books Result

books.google.com.tw/books?isbn=0766190013

Aylmer Maude - 2004 - Biography & Autobiography

and to-day we are told by many that art has nothing to do with morality — that art should ... I went one day, with a lady artist, to the Bodkin Art Gallery, in Moscow.第十卷

本卷包括根據英國倍因(Robert Nisbet Bain,通譯貝恩)的英譯本Russian Fairy Tales(一八九二年)選譯的《俄羅斯民間故事》,根據培因(即倍因)的英譯本Cossack Fairy Tales and Folk-Tales(一八九四年)選譯的《烏克蘭民間故事》,根據英國韋格耳(Arthur Edward Pearse Brome Weigall,通譯韋戈爾)所著傳記Sappho of Lesbos: Her Life and Times (一九三二年)編譯的《希臘女詩人薩波》,英國勞斯(William Henry Denham Rouse)著神話故事《希臘的神與英雄》(Gods, Heroes and Men of Ancient Greece,一九三四年),以及“其他英文和世界語譯作”。

《俄羅斯民間故事》譯於一九五二年五月,一九五二年十一月由香港大公書局出版,署“知堂譯”。一九五七年八月天津人民出版社重印此書,署“周啟明譯”。

"I asked myself: 'Is it possible to love a woman who will never understand the profoundest interests of my life? Is it possible to love a woman simply for her beauty, to love the statue of a woman?' But I was already in love with her, though I did not yet trust to my feeling."

--from "The Cossacks" by Leo Tolstoy

Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy was born at Yasnaya Polyana, a family estate located near Tula, Russia on this day in 1828.

“Olenin always took his own path and had an unconscious objection to the beaten tracks.”

― Leo Tolstoy, The Cossacks

― Leo Tolstoy, The Cossacks

2018年11月3日 星期六

War and peaceful gardens: in the land of Tolstoy. BBC:Pernicious Ambition and Tolstoy’s “War and Peace”

"The cudgel of the people's war was lifted with all its menacing and majestic might, and caring nothing for good taste and procedure, with dull-witted simplicity but sound judgement it rose and fell, making no distinctions." - Leo Tolstoy

Have you ever wanted to read 'War and Peace' but find this magnificent novel somewhat daunting? Our audio guide presented by Amy Mandelker suggests ways of approaching this masterpiece for first-time readers. Amy is Associate Professor of Comparative Literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

"Perhaps having intuited Tolstoy’s disdain for ambition, the creators of the BBC series focused most of their attention on the realm of home. The disease of Napoleonism is largely absent from the Davies adaptation, where Napoleon emerges as a pedestrian villain. In minimizing Napoleon and the Napoleonic quest, the series’s directors domesticate male characters, robbing them of the outward ambition so apparent in Tolstoy’s novel: Andrei (James Norton) seems bored and restless, while Pierre’s (Paul Dano) primary motivation appears to be a very contemporary kind of anxiety."

Ani Kokobobo laments the muting of Napoleonism in the latest adaptation of…

LAREVIEWOFBOOKS.ORG

東方白的文學回憶錄【真與美】末卷,有專文介紹他與夫人訪此莊園的感動........

War and peaceful gardens: in the land of Tolstoy

A visit to Tolstoy’s country estate gives writer and gardener Charlotte Mendelson an insight into the relationship between nature and creativity

Country life … Tolstoy in the grounds of his estate, Yasnaya Polyana. Photograph: George Rinhart/Corbis/Getty

Country life … Tolstoy in the grounds of his estate, Yasnaya Polyana. Photograph: George Rinhart/Corbis/GettyCharlotte Mendelson

Saturday 15 October 2016 11.00 BST

Springtime can kill you, but autumn is worse. If one’s soul responds to nature – and, as Louis Armstrong said of jazz, if you have to ask what that means, you’ll never know – then its beauty is painful. Whatever TS Eliot thought (the poor man was wrong about so much), autumn is the most painful time of all. Walking in the grounds of Tolstoy’s country estate at Yasnaya Polyana, yellow birch leaves turning gently as they fall, is almost too much, particularly for an oversensitive novelist. Five of us are here, imported by the British Council to broaden Russian conceptions of British literature. We have worked – by God we have worked – but, this morning, among the wooded paths and ripe, rich leaf mould, nothing else seems to matter, not even fiction.

For cramped city-dwellers, the incomprehensible excess of space is dazzling: the “cascade of three ponds”, each more invitingly cool and swimmable than the last; the fir woods thick with fungal life; the juicy grass. Even the ponies have had a surfeit. There is so much silken birch bark, pinkly tender beneath its epidermis; so many fallen, unregarded apples and ancient, lichen-spattered branches: mustard, pigeon, rose. One wants to sniff and wallow; at least, I do. Surely this is normal? A reasonable response to being knee-deep in the dew and bracken: surrendering to the space, the wildness?

Of course not. My fellow writers return home with translators’ business cards and ecclesiastical souvenirs. My case is full of Japanese quinces, oak leaves, almond shells, calendula seeds and, most worrying of all, a knobbly fir branch, as long as my arm, stolen from the forest floor and slipped past the cold-eyed, epauletted customs boys at Domodedovo airport. Did the other novelists find themselves embarrassingly weeping at the perfect transparency of a plantation of firs, bare-trunked and widely spaced to allow, as Sofia and Leo Tolstoy had intended, the pale September sunlight to pour in? They did not.

***

Like his grandfather, Prince Volkonsky, who first developed the estate in Tula region, 120 miles south of Moscow, Leo Tolstoy was an enthusiast. His wife, Sofia, may also have been, in her spare moments between bearing his 13 children, copying and editing War and Peace seven times and documenting every minute of their lives in diaries and photographs. Sofia’s husband had no time for such fripperies. He was busy, trying to create a new breed of horse by crossing English thoroughbred stallions with their Kirgizian cousins; following developments in fruit-tree breeding; buying Japanese pigs (“I feel I cannot be happy in life until I get some of my own”); downing healthy bowlfuls of fermented mare’s milk; maddening Sofia with his “purely verbal” renunciation of worldly goods; spending too many roubles on attempting to grow watermelons, coffee and pineapples in his hothouse. Anything, one suspects, could have captured his attention: dog-racing, topiary, needlepoint.

Tolstoy derided his early works as an awkward mixture of fact and fiction, yet they offer an insight into what made him

But, although it’s easy to dismiss him as a Professor Branestawm crank, to laugh at the old man who lifted weights in his study and hung, red-faced, from a bar while instructing his staff, Tolstoy’s passionate engagement with the land around him was his life’s joy. Like all but the unluckiest children, even today, he knew the tannic bite of currant leaves, the rumpled gloss of worm casts, the hayish sweetness of a grass stem. Childhood, boyhood, youth is thick with the sensual thrills of the outdoors: the damply shaded raspberry thicket, alive with sparrows, and the taste of accidentally ingested wood beetles, the cobwebs, the dense, dank soil. And, even though he famously derided his early works as “an awkward mixture of fact and fiction”, they offer a moving insight into what made him.

Monet wrote: “Je dois peut-être aux fleurs d’avoir été peintre” – I perhaps owe having become a painter to flowers. Writers are often asked what made them write; I can’t answer that for myself, let alone for Monet, but, surely, the intense feelings evoked by colour and form made him need to express himself, in paint. He also became a wonderful gardener. Edith Wharton’s first published short story, Mrs Manstey’s View, describes how a glimpse of shabby town garden is all that keeps old Mrs Mantsey alive. Later, of the grand Italianate gardens, all rustic rock fountains and pleaching, which she designed for The Mount, her home in Massachusetts, she wrote: “I’m a better landscape gardener than novelist, and this place, every line of which is my own work, far surpasses The House of Mirth.”

Wharton was wrong about the novels, and The Mount is too neat for me: where is the sledge requisitioned as a plant crutch? However, we would agree, I think, about the soothing power of gardens: loneliness and sadness are horrible, but they feed us, teach us to comfort ourselves with alertness, and to look – what the poet Mary Oliver calls paying attention. When at school I encountered Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “worlds of wanwood leafmeal” in “Spring and Fall: To a Young Child”, or Laurie Lee’s morning in “April Rise” – “lemon-green the vaporous morning drips / wet sunlight on the powder of my eye” – I recognised that precision, the thrilling focus on nature, close up. Don’t other children, on the rare occasions when they’re not reading, fall in love with the blistered, sun-warmed paint on a door, the beauty of old, lichened bricks, or susurrating grasses? We didn’t have grateful serfs or 100 acres of orchards, but there were new worlds among the wild strawberries and, possibly, ichthyosaur bones in the sandpit.

I had no interest in gardens until my mid-30s but, I now realise, I had fallen in love with leaves, twigs and decay long ago, and it made me need to write. Tolstoy may have found apiaries so absorbing, he claimed he could barely remember the author of The Cossacksbut, as he told an old friend: “Whatever I do, somewhere between the dung and the dirt I keep starting to weave words.”

***Count Tolstoy would probably not have recognised my tiny outdoor space as a garden. Largely paved, entirely overlooked, without bluebells or coppicing or even a simple wildflower meadow, my six square metres of polluted soil he would consider to be unworthy of the most pitiful peasant schoolteacher: where is the pig? The walnut tree? Oh Leo, I know; I’m disappointed too.

This may be why, for me, garden writing is a sensitive subject. As a writer and a gardener, albeit of an experimental jungle allotment, the classics of domestic horticulture leave me embarrassingly cold. Gertrude Jekyll, Elizabeth von Arnim, Margery Fish, Mirabel Osler, even Christopher Lloyd, the Mae West of garden writers, all had acres, staff, greenhice. Their vision was inspiring, their metaphors exciting (I particularly love Lloyd’s division of smells into “moral and immoral”), but their rambling rhododendron groves and stone walkways were alienating to a novice. Reading about their tree‑surgery crises was like owning a carnivorous Shetland pony while reading about Olympic dressage: all very lovely but not for the likes of me. Besides, my ever more rampaging obsession was for growing fruit and vegetables, now well over 100 different kinds and the more unusual the better, yet most garden writing focused either on shrubbery and flowers, or on an alien world of double digging potato trenches, superphosphate and basic pruning, apparently a simple twice-yearly process of shortening main central leaders, side-branch leaders to the third tier and laterals, then spurring back and tying in, which, to a person unable to tell their left from their right, was of limited value.

At the other end of the gamut of garden writing lies seed catalogues: during times of stress or in deepest midwinter, they are perfect for reading in the bath. At least, they should be. But, for the novelist-gardener, trauma lies ahead. I hope I am not alone in finding certain words and phrases unbearable: “veggies”, “a bake”, “eat happy”, “hue”. Unfortunately, seed catalogues are worse, full of showy choice fluoroselect picotee bicoloured collarette pastel novelties. Perfectly ordinary varieties of flowers, fruit and vegetables bear names for which there is no excuse: Naughty Marietta, Slap ’n’ Tickle, Tendersnax, Bright Bikini, Nonstop® Rose Petticoat. They make me want to die.

Noël Coward described Vita Sackville-West as 'Lady Chatterley above the waist and the gamekeeper below'

And so, needing both comradeship and advice, I have found my gardening friends in unlikely places: horticulturally minded food writers; Joy Larkcom’s and her masterpiece, Oriental Vegetables; poor murdered Karel Čapek, author of my beloved The Gardener’s Year; and Ursula Buchan’s Garden People, for sartorial guidance. Who needs advice about vine weevils when one can gaze at photographs of interior designer and gardener Nancy Lancaster’s sexy yellow scarf, or the rakish gaucho hat of Rhoda, Lady Birley, as she firmly grips those scarlet parrot-bill loppers? Noël Coward described Vita Sackville-West as “Lady Chatterley above the waist and the gamekeeper below”, which is good enough for me.

And now, after a decade of increasingly demented growing, I have at last found my gardening sibling: Leo Tolstoy. At Yasnaya Polyana, inspecting the fat yellow squashes growing on the compost heap, sensing the curvature of the earth as we reached the bare brim of a wooded hill, I suddenly understood that in one respect, if, irritatingly, none other, I and the great beardy genius are alike. We are enthusiasts. Fine, so my garden isn’t an arrangement of colours and textures to please an artist’s, or even a normal gardener’s, eye. Who cares if it’s not reflected in any book I’ve read, or if few others garden purely for taste, smell, sensual pleasure: the warm pepper of tomato leaves, curling courgette tendrils, the corduroy ridges on a coriander seed. My tiny green and fragrant world would definitely not have been admired by Tolstoy’s guests from the drawing-room windows, but I think the man himself would have understood the passion behind it. Please ignore the broom handles and recycled windows; I’m sorry that there is nowhere to sit. But just taste this Crimean tomato, this purple bean, this golden raspberry. Look into the translucent depths of this whitecurrant. Pay attention. It brings such peace.

• Rhapsody in Green is published by Kyle Books. To order a copy for £12.99 (RRP £16.99) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.

Monet wrote: “Je dois peut-être aux fleurs d’avoir été peintre” – I perhaps owe having become a painter to flowers. Writers are often asked what made them write; I can’t answer that for myself, let alone for Monet, but, surely, the intense feelings evoked by colour and form made him need to express himself, in paint. He also became a wonderful gardener. Edith Wharton’s first published short story, Mrs Manstey’s View, describes how a glimpse of shabby town garden is all that keeps old Mrs Mantsey alive. Later, of the grand Italianate gardens, all rustic rock fountains and pleaching, which she designed for The Mount, her home in Massachusetts, she wrote: “I’m a better landscape gardener than novelist, and this place, every line of which is my own work, far surpasses The House of Mirth.”

Wharton was wrong about the novels, and The Mount is too neat for me: where is the sledge requisitioned as a plant crutch? However, we would agree, I think, about the soothing power of gardens: loneliness and sadness are horrible, but they feed us, teach us to comfort ourselves with alertness, and to look – what the poet Mary Oliver calls paying attention. When at school I encountered Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “worlds of wanwood leafmeal” in “Spring and Fall: To a Young Child”, or Laurie Lee’s morning in “April Rise” – “lemon-green the vaporous morning drips / wet sunlight on the powder of my eye” – I recognised that precision, the thrilling focus on nature, close up. Don’t other children, on the rare occasions when they’re not reading, fall in love with the blistered, sun-warmed paint on a door, the beauty of old, lichened bricks, or susurrating grasses? We didn’t have grateful serfs or 100 acres of orchards, but there were new worlds among the wild strawberries and, possibly, ichthyosaur bones in the sandpit.

I had no interest in gardens until my mid-30s but, I now realise, I had fallen in love with leaves, twigs and decay long ago, and it made me need to write. Tolstoy may have found apiaries so absorbing, he claimed he could barely remember the author of The Cossacksbut, as he told an old friend: “Whatever I do, somewhere between the dung and the dirt I keep starting to weave words.”

***Count Tolstoy would probably not have recognised my tiny outdoor space as a garden. Largely paved, entirely overlooked, without bluebells or coppicing or even a simple wildflower meadow, my six square metres of polluted soil he would consider to be unworthy of the most pitiful peasant schoolteacher: where is the pig? The walnut tree? Oh Leo, I know; I’m disappointed too.

This may be why, for me, garden writing is a sensitive subject. As a writer and a gardener, albeit of an experimental jungle allotment, the classics of domestic horticulture leave me embarrassingly cold. Gertrude Jekyll, Elizabeth von Arnim, Margery Fish, Mirabel Osler, even Christopher Lloyd, the Mae West of garden writers, all had acres, staff, greenhice. Their vision was inspiring, their metaphors exciting (I particularly love Lloyd’s division of smells into “moral and immoral”), but their rambling rhododendron groves and stone walkways were alienating to a novice. Reading about their tree‑surgery crises was like owning a carnivorous Shetland pony while reading about Olympic dressage: all very lovely but not for the likes of me. Besides, my ever more rampaging obsession was for growing fruit and vegetables, now well over 100 different kinds and the more unusual the better, yet most garden writing focused either on shrubbery and flowers, or on an alien world of double digging potato trenches, superphosphate and basic pruning, apparently a simple twice-yearly process of shortening main central leaders, side-branch leaders to the third tier and laterals, then spurring back and tying in, which, to a person unable to tell their left from their right, was of limited value.

At the other end of the gamut of garden writing lies seed catalogues: during times of stress or in deepest midwinter, they are perfect for reading in the bath. At least, they should be. But, for the novelist-gardener, trauma lies ahead. I hope I am not alone in finding certain words and phrases unbearable: “veggies”, “a bake”, “eat happy”, “hue”. Unfortunately, seed catalogues are worse, full of showy choice fluoroselect picotee bicoloured collarette pastel novelties. Perfectly ordinary varieties of flowers, fruit and vegetables bear names for which there is no excuse: Naughty Marietta, Slap ’n’ Tickle, Tendersnax, Bright Bikini, Nonstop® Rose Petticoat. They make me want to die.

Noël Coward described Vita Sackville-West as 'Lady Chatterley above the waist and the gamekeeper below'

And so, needing both comradeship and advice, I have found my gardening friends in unlikely places: horticulturally minded food writers; Joy Larkcom’s and her masterpiece, Oriental Vegetables; poor murdered Karel Čapek, author of my beloved The Gardener’s Year; and Ursula Buchan’s Garden People, for sartorial guidance. Who needs advice about vine weevils when one can gaze at photographs of interior designer and gardener Nancy Lancaster’s sexy yellow scarf, or the rakish gaucho hat of Rhoda, Lady Birley, as she firmly grips those scarlet parrot-bill loppers? Noël Coward described Vita Sackville-West as “Lady Chatterley above the waist and the gamekeeper below”, which is good enough for me.

And now, after a decade of increasingly demented growing, I have at last found my gardening sibling: Leo Tolstoy. At Yasnaya Polyana, inspecting the fat yellow squashes growing on the compost heap, sensing the curvature of the earth as we reached the bare brim of a wooded hill, I suddenly understood that in one respect, if, irritatingly, none other, I and the great beardy genius are alike. We are enthusiasts. Fine, so my garden isn’t an arrangement of colours and textures to please an artist’s, or even a normal gardener’s, eye. Who cares if it’s not reflected in any book I’ve read, or if few others garden purely for taste, smell, sensual pleasure: the warm pepper of tomato leaves, curling courgette tendrils, the corduroy ridges on a coriander seed. My tiny green and fragrant world would definitely not have been admired by Tolstoy’s guests from the drawing-room windows, but I think the man himself would have understood the passion behind it. Please ignore the broom handles and recycled windows; I’m sorry that there is nowhere to sit. But just taste this Crimean tomato, this purple bean, this golden raspberry. Look into the translucent depths of this whitecurrant. Pay attention. It brings such peace.

• Rhapsody in Green is published by Kyle Books. To order a copy for £12.99 (RRP £16.99) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.

2015年9月23日 星期三

Tolstoy's War and Peace , "Anna Karenina"/ Short Fiction (Norton Critical Editions)

"He stepped down, trying not to look long at her, as if she were the sun, yet he saw her, like the sun, even without looking."

--from "Anna Karenina" By Leo Tolstoy

A famous legend surrounding the creation of Anna Karenina tells us that Tolstoy began writing a cautionary tale about adultery and ended up falling in love with his magnificent heroine. It is rare to find a reader of the book who doesn’t experience the same kind of emotional upheaval. Anna Karenina is filled with major and minor characters who exist in their own right and fully embody their mid-nineteenth-century Russian milieu, but it still belongs entirely to the woman whose name it bears, whose portrait is one of the truest ever made by a writer. Translated by Louise and Aylmer Maude.

Leo Tolstoy’s short works, like his novels, show readers his narrative genius, keen observation, and historical acumen—albeit on a smaller scale. This Norton Critical Edition presents twelve of Tolstoy’s best-known stories, based on the Louise and Aylmer Maude translations (except “Alyosha Gorshok”), which have been revised by the editor for enhanced comprehension and annotated for student readers. The Second Edition newly includes “A Prisoner in the Caucasus,” “Father Sergius,” and “After the Ball,” in addition to Michael Katz’s new translation of “Alyosha Gorshok.” Together these stories represent the best of the author’s short fiction before War and Peace and after Anna Karenina.

“Backgrounds and Sources” includes two Tolstoy memoirs, A History of Yesterday (1851) and The Memoirs of a Madman (1884), as well as entries—expanded in the Second Edition—from Tolstoy’s “Diary for 1855” and selected letters (1858–95) that shed light on the author’s creative process.

“Criticism” collects twenty-three essays by Russian and western scholars, six of which are new to this Second Edition. Interpretations focus both on Tolstoy’s language and art and on specific themes and motifs in individual stories. Contributors include John M. Kopper, Gary Saul Morson, N. G. Chernyshevsky, Mikhail Bakhtin, Harsha Ram, John Bayley, Vladimir Nabokov, Ruth Rischin, Margaret Ziolkowski, and Donald Barthelme.

A Chronology of Tolstoy’s life and work and an updated Selected Bibliography are also included.

. --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Language Notes

Text: English (translation)

Original Language: Russian

Original Language: Russian

Product Details

- Paperback: 503 pages

- Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company (January 1991)

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

2010年12月4日 星期六

War and Peace I 戰爭與和平

中文本約40年前讀過

之所以買它 因為多年前有一下冊

本書有地圖 幫助會很大

War and Peace (Oxford World's Classics)

More than a historical chronicle of Russia's struggle with Napoleon, War and Peace is a record of the lives of individuals involved, of the physical realities of human experience, in short, a complete portrait of the human experience--from happiness and greatness, to grief and humiliation. This new one-volume edition replaces the two paperback volumes in the World's Classics first published in 1983.

重要書評

除了稱他為最偉大的小說家之外,我們還能怎麼來稱呼戰爭與和平的作者?-維吉尼亞‧吳爾芙

《戰爭與和平》是世界上最偉大的小說--英國作家毛姆

此書應自天上來,非人間可得--德國小說家赫曼‧赫塞

《戰爭與和平》是我們時代裡最偉大的史詩,是近代的伊利亞特--羅曼‧羅蘭

自稱對文學有「狂戀式的愛情」的托爾斯泰,前後耗費十餘年的光陰,才完成這部劃時代的鉅著。《戰爭與和平》主要以1812年拿破崙侵俄的戰爭為中心,敘 述三個俄羅斯貴族家族,在戰爭與和平的年代裡,經歷生活中無數的苦痛後,終於體驗出人生真諦的故事,同時隨著主角的命運軌跡,展露出19世紀初期俄國社會 與政治變遷的形形色色,記下歐洲歷史最動盪的時期,氣勢恢宏澎湃,無以倫比。

托爾斯泰作品最大的特色便是運用寫實主義和心理分析的手 法。在《戰爭與和平》中,人物就多達559個,每一個都是活生生的血肉之軀,各有其獨特的個性,且充滿了生命的悸動,恐怕只有莎士比亞的作品可以媲美。而 書中史詩般的輝煌節奏與寬闊視界,也只有荷馬的作品可以相較。

作者簡介

列夫‧托爾斯泰(Leo Tolstoy,1828-1910),公認為最偉大的俄國文學家,《西方正典》作者哈洛‧卜倫甚至稱之為「從文藝復興以來,唯一能挑戰荷馬、但丁與莎士比亞的偉大作家」。 曾參加克里米亞戰爭,戰後漫遊法、德等國,返鄉後興辦學校,提倡無抵抗主義及人道主義。創作甚豐,皆真實反映俄國社會生活,除著名的長篇小說《戰爭與和 平》、《安娜.卡列尼娜》之外,另有自傳體小說《童年‧少年‧青年》和數十篇中短篇小說,以及劇本、書信、日記、論文等等。

譯者簡介

草嬰(1923- ),本名盛峻峰,15歲開始學習俄語,1952年起為人民文學出版社等翻譯俄國文學。現任華東師範大學和廈門大學教授、上海譯文出版社編譯、中國作家協會 外國文學委員會委員等。1987年在莫斯科榮獲「高爾基文學獎」,主要譯作包括「托爾斯泰小說全集」、肖洛霍夫《一個人的遭遇》等。

之所以買它 因為多年前有一下冊

本書有地圖 幫助會很大

War and Peace (Oxford World's Classics)

(ISBN: 0192833987 / 0-19-283398-7 )

Leo Tolstoy

Review

'there are pages of useful information making this volume the ideal vehicle to introduce the general reader to Tolstoy's epic ... the whole novel is here contained in one single volume ... so well bound that it will lie open at any page - an admirable quality in any book but rare to find in a paperback' Jean Fyfe, Scottish Slavonic Review, No. 20, 1993More than a historical chronicle of Russia's struggle with Napoleon, War and Peace is a record of the lives of individuals involved, of the physical realities of human experience, in short, a complete portrait of the human experience--from happiness and greatness, to grief and humiliation. This new one-volume edition replaces the two paperback volumes in the World's Classics first published in 1983.

戰爭與和平(上) War and Peace

- 作者:列夫‧托爾斯泰/著

- 原文作者:Leo Tolstoy

- 譯者:草嬰

- 出版社:木馬文化

- 出版日期:2004年07月02日

重要書評

除了稱他為最偉大的小說家之外,我們還能怎麼來稱呼戰爭與和平的作者?-維吉尼亞‧吳爾芙

《戰爭與和平》是世界上最偉大的小說--英國作家毛姆

此書應自天上來,非人間可得--德國小說家赫曼‧赫塞

《戰爭與和平》是我們時代裡最偉大的史詩,是近代的伊利亞特--羅曼‧羅蘭

自稱對文學有「狂戀式的愛情」的托爾斯泰,前後耗費十餘年的光陰,才完成這部劃時代的鉅著。《戰爭與和平》主要以1812年拿破崙侵俄的戰爭為中心,敘 述三個俄羅斯貴族家族,在戰爭與和平的年代裡,經歷生活中無數的苦痛後,終於體驗出人生真諦的故事,同時隨著主角的命運軌跡,展露出19世紀初期俄國社會 與政治變遷的形形色色,記下歐洲歷史最動盪的時期,氣勢恢宏澎湃,無以倫比。

托爾斯泰作品最大的特色便是運用寫實主義和心理分析的手 法。在《戰爭與和平》中,人物就多達559個,每一個都是活生生的血肉之軀,各有其獨特的個性,且充滿了生命的悸動,恐怕只有莎士比亞的作品可以媲美。而 書中史詩般的輝煌節奏與寬闊視界,也只有荷馬的作品可以相較。

作者簡介

列夫‧托爾斯泰(Leo Tolstoy,1828-1910),公認為最偉大的俄國文學家,《西方正典》作者哈洛‧卜倫甚至稱之為「從文藝復興以來,唯一能挑戰荷馬、但丁與莎士比亞的偉大作家」。 曾參加克里米亞戰爭,戰後漫遊法、德等國,返鄉後興辦學校,提倡無抵抗主義及人道主義。創作甚豐,皆真實反映俄國社會生活,除著名的長篇小說《戰爭與和 平》、《安娜.卡列尼娜》之外,另有自傳體小說《童年‧少年‧青年》和數十篇中短篇小說,以及劇本、書信、日記、論文等等。

譯者簡介

草嬰(1923- ),本名盛峻峰,15歲開始學習俄語,1952年起為人民文學出版社等翻譯俄國文學。現任華東師範大學和廈門大學教授、上海譯文出版社編譯、中國作家協會 外國文學委員會委員等。1987年在莫斯科榮獲「高爾基文學獎」,主要譯作包括「托爾斯泰小說全集」、肖洛霍夫《一個人的遭遇》等。

No comments:

Post a Comment